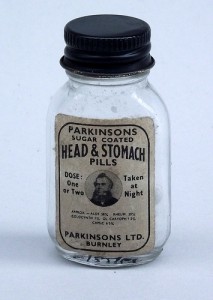

Photo courtesy of https://flic.kr/ps/q5KAv

You have heard of the placebo response and have a general idea of how it works. The reality is that few of us know just how powerful it is.

This wouldn’t be a problem except that most drugs, when studied in clinical trials, are compared to placebo. This means that patient beliefs during treatment may have much stronger effects than the drug itself. Many drugs are studied under double-blind placebo controlled studies in the attempt to control for the placebo response. In these studies, neither the reviewer (many times this is the treating physician) nor the patient knows who is taking the placebo and who is taking the active drug. But if the patient even thinks he or she is on the active drug, it can completely throw off the results of the study.

In single-blind studies, the reviewer knows whether or not the patient is on the placebo or drug. This requires the reviewer to maintain an absolutely neutral attitude towards the patient lest he or she gives a hint as to what arm of the study the patient is in.

In non-blinded studies, all bets are off.

Although I don’t have the reference I remember coming across a study on blood pressure medications. The sneaky design of the study had participants believing that the study was designed to compare the drug to the placebo. In the study, the placebo had a pretty powerful response and the drug response was only a little bit stronger. However, when researchers teased apart those who were most compliant with taking the pills, whether drug or placebo, had the strongest blood pressure response. From compliance, we can conjecture that those who took the pills as prescribed had a much deeper belief that it was going to help them. This belief trumped all as far as a treatment response.

With that being said about the power of placebo, the opposite can also be true. This is called the nocebo response and deals with patients who have negative expectations for treatment or side effects. In other words, if you hear from your doctor that Drug A has some pretty nasty side effects, you are actually more likely to experience said side effects.

This particular study will completely destroy your faith in the ability to truly study the benefit of any drug in any study.

In it, researchers took 66 chronic migraine sufferers and followed them from an initial migraine attack through the next 6 attacks. In each of the attacks (after the initial attack for which no treatment was given, which served as the control), participants were given either a placebo or Maxalt (10-mg rizatriptan) over the course of the next 459 attacks.

(Editor’s note: due to the nature of this article, I will not go into the correct approach to the management and elimination of migraines. Feel free to check out my Migraines and Epilepsy eBook for that…)

What made this trial different was what was communicated to the migraine sufferer. The treatment was given under three different information conditions:

- Negative—they were given and told they were given a placebo

- Neutral—they were given and told they were given Maxalt

- Positive—they were given placebo but told it was Maxalt.

Pretty clever (but sneaky) if you ask me. Here’s what the researchers found out:

- Response to Maxalt was stronger than placebo (not unexpected).

- The placebo response was stronger than no treatment (not unexpected either).

- The placebo, even when the patients were told it was a placebo, had a stronger response then no treatment (a wee bit of a surprise here…)

- When participants were given placebo labeled as (i) placebo, (ii) Maxalt or placebo, and (iii) Maxalt, the overall placebo effect increased.

- Maxalt had a similar progressive boost when labeled with these three labels.

- The response to Maxalt labeled as a placebo and placebo labeled as Maxalt were similar.

- Compared to no treatment, the placebo, under each information condition, resulted in more than 50% of the drug effect.

This is really interesting stuff. Basically, the more “positive” information the patient got, the stronger the response, regardless of whether it was a drug or placebo. The reverse was also true—if the patients did not believe they were given the drug the response was not as strong.

This says a few things about society and can help me as a physician. First, a note on society. And it’s a sad note. This study found that, even if patients were told they were given a placebo that we all know is “just a sugar pill” our programming that drugs “fix things” runs so incredibly deep that merely taking a pill has the potential to help EVEN when we know it can’t possibly help.

More importantly, I know that, as a physician, my beliefs and reassurances about the treatments I offer have a strong impact on the outcomes of these same treatments. My assurance to a patient that a treatment for his or her condition can be very effective can be as powerful as the treatment itself. Ironically, with experience and seeing thousands of patients over the years benefit, I become more confident in the treatment I provide. This confidence can, in turn, improve the outcomes of my patients. Pretty cool.